Can Twitterbots Improve Public Health? An Interview with Jonathan Noel

Assistant professor Jonathan Noel, PhD, decided to go into the field of public health when he saw how creating the right policies and programs could improve the health of millions of people. He's been involved in evaluation studies on alcohol advertising within social media. And what he's learned might change the way public health campaigns are delivered — and more importantly, improve people's health.

Tell me a little bit about yourself. How did you first get interested in public health?

When I started, I was on a pre-med track — I thought I was going to be a doctor. But when I was a sophomore in college, I trained as an EMT to get experience working with patients. And I did not like it at all. I was doing the work — I remember doing chest compressions on a guy in the back of an ambulance zooming off to the hospital — but there was no passion behind it. I still wanted to be in the health field, so I emailed the Department of Public Health in Connecticut. And they signed me up to do a summer internship. I ended up spending the summer between my junior and senior year working on endemic influenza. That was the year that everyone was freaking out about bird flu. And that’s when I realized you could impact a lot of people, millions of people, by making a few decisions either the right way or the wrong way. If I can get the right program in place, the right policy in place, I can impact millions of people simultaneously. That ended up being the draw.

I read that you’re doing evaluation studies on advertising in social media. How did you get interested in that?

When I was doing my masters of Public Health, I worked for this researcher who was in the middle of a project evaluating beer advertising during the NCAA basketball tournaments. That got me on to, “well, if I kind of like this policy program stuff, what are the things pushing back against these policies?” And in this case, the alcohol industry was a big one, because you’re trying create an alcohol-abuse policy and the messages they’re putting out are basically “drink as much as you want and you’ll be fine.” So that got me interested.

"At this point we’re trying to do a little “name and shame” — call out the companies and call out the brand."

There's this video ad I saw on Facebook for a belt buckle that flipped open to become sort of a cup holder for beer. And I noticed that the models in the video were super young looking. They looked like they were 18, if that.

Alcohol marketing in the US is not really regulated. Basically, the companies have made these promises. And all the research that I’ve been a part of is comparing their marketing to their promises. And what comes out is, no, you are not living up to anything that you said you would do. And the age of the actors and actresses is one of them. [The alcohol industry] promised that none of the actors and actresses will be younger than 25 years old. And that none of them should look younger than 21. But in reality, half of them look younger than 21. They could be 40 years old, we don’t care, but if they’re perceived as being underage…that’s what we’re trying to avoid.

So at this point we’re trying to do a little “name and shame” — call out the companies and call out the brand. And we’re using data to really promote stronger policies.

When you say, “we,” who do you mean?

My old advisor, Dr. [Thomas] Babor — he’s one of the leaders in trying to evaluate this type of marketing. Through him, I’ve been able to get in touch with multiple researchers around the US and around the world. I was part of one group that published a series of papers earlier this year specifically devoted to this topic. And I’m part of a separate group doing something very similar, taking a broader view to try to sway the discussion.

"A drink a day isn’t going to make you healthier."

What will it take to make changes?

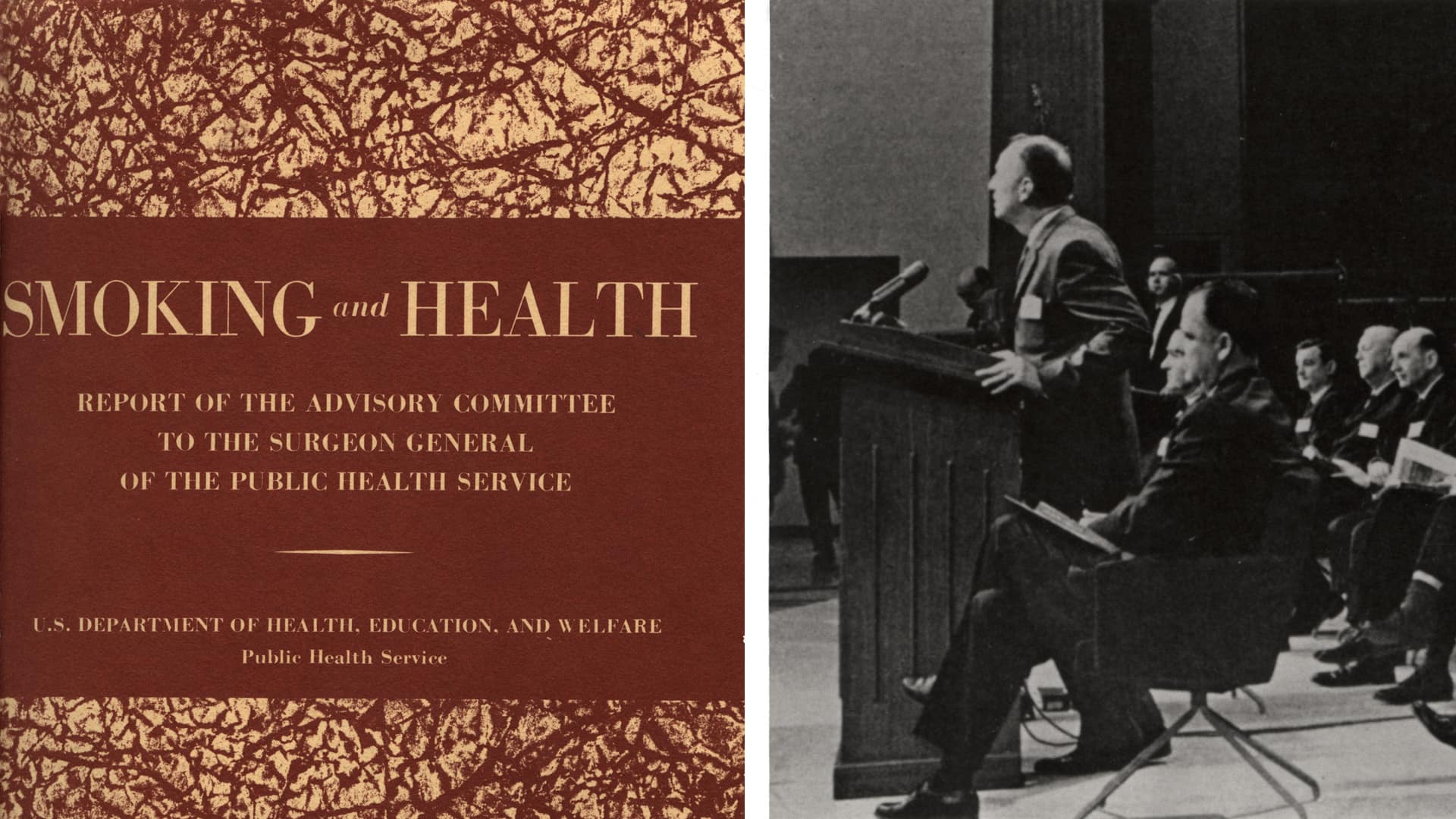

It’s going to take time. Time and a couple of really lucky breaks. Look at the big changes we’ve seen in tobacco: one, it took decades. The first Surgeon General report came out in 1964 and it wasn’t until the 90s that we had really good action. Two, it was also the lawsuits. So once we had the internal documents saying tobacco companies knew nicotine was addictive and knew they were marketing to children, then we had more of a standing to go after them.

| (L) The landmark 1964 Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health, 1964; (R) Surgeon General Luther Terry presents findings at press conference. |

So you didn’t have to worry about getting sued?

It wasn’t necessarily that — it was also public perception. Even now there’s still the vast perception that a drink a day is okay when it’s not necessarily okay.

Really?

Yes, it's new research. It hasn’t necessarily been widespread yet, but you know, a drink a day isn’t going to make you healthier. It may not harm you, but it’s not going to help you live longer. It’s not going to help your heart disease.

Not even red wine?

No. Those were flawed studies. Basically, when they did the original research studies, they grouped the people who didn’t drink with people who couldn’t drink for a specific health reason. For example, they were former alcoholics, so they didn’t drink anymore or they had some other disease condition where they couldn’t drink. So it drove their health risks higher. They put the people with diseases into the non-drinking group among the lifetime non-drinkers. And it made them look a lot worse than they really were.

Are they doing new studies?

They’re always doing new studies. There’s actually a study right now being funded by the alcohol industry. So we’re very curious about how close they’re monitoring their work and how much influence they’ll have. They're doing it in a very insidious way — they're actually giving money to the National Institutes of Health and the money is flowing out of that group to researchers. And it's a five-year study to determine if a drink a day will make you healthier. But we’re reasonably confident there’ll be no effect, but we'll see if there is some effect that they’ll caveat in a bunch of ways to make it look like there’s some effect.

The Nurses’ Health Study didn’t cover alcohol?

I don’t know if the Nurses’ Health Study came out with it…I’ll have to look into that. I'm sure it was published on. But again, it all depends on how you define your control group: Who are your non-drinkers?

Do you cover how to set up valid studies in the classes you teach?

We start with the basics. So, in the Intro to Public Health class, we introduce the basics of research methods: what are the basic designs, what sort of control groups can you have, what types of interventions are involved.

What do you see as the biggest issues in public health?

On my first day of class, I ask my Intro to Public Health students that: what are the seven biggest public health problems we have right now? I put them all into groups and they come up the big ones. They talk about the obesity epidemic, the opioid epidemic. One or two groups will mention heart disease, they’ll mention cancer. But there are kind of larger structural issues that go into the social determinants of health which can impact a lot of things, such as reinforcing and stabilizing the Affordable Care Act. And making sure that doesn’t get repealed, so it’s a political advocacy issue. And I admit to my students that I get on my soapbox sometimes, as we all tend to do, but I talk about the tax reform bill and how this will impact people. You might not think this has health impacts, but in fact, it will have huge health impacts.

On top of that there are some very basic public health issues, such as clean water. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan is not that old — they're still dealing with it. I show my classes a couple of videos when I talk about environmental health on fracking, where methane can seep into the water supply. One is a video of a woman lighting her tap water on fire because of the methane gas. We’re still dealing with clean air issues. In certain parts around the US and certainly other parts around the world are just terrible. You can literally see the smog rolling in and out of certain cities. And it's fascinating in a terrible way that in the developing world, there are countries that are simultaneously dealing with malnutrition and obesity, and the chronic diseases that are associated with obesity. It’s because you have the urban centers that have been westernized, but then you have the rural regions that don’t have access to basically any resources that we can take advantage of.

"There are no small public health issues."

So there are these pockets of populations with different issues within the same country?

Yes, there are all of these disparities, and also between the US and the rest of the world. I try to bring in both — I try not to just focus on the US, as we tend to do. But there's a lot. That’s the problem, that they are all big issues. There are no small public health issues. Even this year's flu season. It was being reported that this year’s vaccine is probably not as effective as you think it is, the strain seems to be tougher, it’s mutated slightly, so it’s probably going to be a worse flu season than in the past couple of years.

That's why you have to specialize and pick what you want to focus on.

What kind of student do you think will do well in our Public Health program?

A student's going to do well if they’re willing to do more than memorize what’s on a page. Students in Public Health and Health Science typically want to both go into public health but also want to be physicians and PAs, and PTs. They may have to memorize tons of stuff. But the people I remember from my Public Health program who are going out into the field as sanitarians and health directors and epidemiologists have to apply this stuff on a day to day basis. So those are the students who will do best: they want to go beyond what’s just in the book and really apply the information in the field.

Have you had any surprising findings in your research?

One of the interesting things — at least I think it's interesting — is research on my dissertation looking at how social media impacts how we perceive a message. When we see a TV ad, we just see the marketing message. We don’t really see anything else. But if I post that up on Facebook, I see other people who commented on it, how many likes it has, how many shares it has, maybe it was shared by one of my friends or has these other endorsements. So I started looking at all these other attributes. At least in my study, it turned out that the comments themselves were almost as impactful at the message. Actually, the comments were going to change people’s intent to drink more than differences in the content of the message. So, what other people are recommending you do and what people are saying about the message on social media may be just as important or even more important than the message itself.

"With basically unleashing Twitterbots for good, you could have really strong public health campaigns."

Interesting. So, it sounds like a little public health army on social media might be helpful.

It can. I’m starting to figure out different ways to study that. But with the technology out there, and with basically unleashing Twitterbots for good, you could potentially have really strong public health campaigns with very little resources. Theoretically you could have an entire health campaign where you never actually post a thing. You just comment on other people’s posts. You could have alcohol moderation or alcohol abstinence messages posted automatically on every alcohol ad published on Facebook. You’d never have to post, you don’t have to create a page, you don't need followers. Someone else carries all the distribution costs, and you just have to craft the right message.

So are you going to do it?

I’m working on the next study to see what would be most effective. We don't have a good public health messaging for alcohol at the moment. We're pretty good on warning labels on tobacco, in the U.S. and in other countries, but not alcohol.

Right. I saw some graphic messaging on cigarette packages in the airport in Montreal this year.

I’ve had students bring me some examples of that from other countries like Brazil and some other Latin American countries and Australia, where they’re actually leading the charge. They not only have graphic warning labels but they have plain packaging so that every cigarette pack looks exactly the same.

So no branding?

No branding at all. They’re all the same drab, olive-gray color. All the font is exactly the same, the same height, the same text. But we have terrible warning labels for alcohol. We know alcohol causes problems. But we don’t have good messaging behind it. And even the recommended guidelines for alcohol use are confusing. So we need a little more work on our messaging before unleashing a big program on the world.